Kostas and the Sterile Male Insect

Part One - Setting the stage for the European War on Mosquitos

Suddenly, it was full of them

It happened last summer, but they still talk about it. Kostas and Elena were receiving some friends at their home in Northern Italy. Eight kids of different ages were running in the garden, shouting as if they had just been released from a week of school. The adults were enjoying the afternoon, calmly sitting in the shade, listening to Elena’s stories about her native rural Poland.

No one could have anticipated the bloody exchange in which they were going to be involved. Or could they? Because the clues were there for the trained eye: the sun was setting, there was no wind, it had rained a week ago, and global temperatures had been gradually increasing in the last decades.

At a certain moment, some internal mechanism switched on in the small body of the many attackers.

Elena felt the first hit in her ankle. She dismissed the idea, thinking: “No, it’s too early, it can’t be that”. But then she heard “SLAP!” A friend had clapped their hands loudly and when they opened them again, there was a splat of blood in the middle. That was it: “They’re coming”.

They didn’t move immediately. That was their mistake. They could have gone inside, but the evening was so delightful, the temperature was perfect, the limoncello was ice-cold. And all of a sudden, it was too late.

CLAP! SPLASH! SLOP! SMASH!

During the next twenty minutes, to the surprise of the kids, all the adults engaged in a crazy tribal dance around the table. On full defensive mode, they were clapping in the air, smashing on the table, getting their hands dirty with small blood stains, pursuing the swarm of little beasts that were eager to saw their veins and suck their blood. They were on a mission to overcome the invasion.

After a while, it just stopped. Some internal mechanism switched off in the small body of the many attackers. They vanished.

With a sense of victory, they counted the victims: they had killed 47 mosquitos.

Reports from the battlefield

Zooming out from Kostas and Elena’s garden, we can see similar confrontations taking place in the whole region. Outdoor dinners are disrupted, money is spent on dubious artefacts to keep mosquitos at bay, ankles get swollen, parents complain to the school teachers that their kids’ legs look like a rosary of bites, and all the teachers give the same puzzled answer: “but we have just been in the garden for 5 minutes”.

From Algeciras to Istanbul, the whole south of Europe is at war with the mosquito.

It’s not only the discomfort. Tropical diseases are hitching a ride and making their comeback in Europe. Get familiar with these names, they might come in handy for your next Scrabble™ game: West Nile Virus, Dengue, Zika, Chikungunya.

Who are these beasts?

Culex pipiens is one, also known as the common mosquito. This is not very frightening as a name.

Aedes albopictus is the other one, also known as the tiger mosquito. Now, that’s what we call good PR.

They divide up the disease load. Dengue, Zika, and Chikungunya travel on board the tiger mosquito. But if you ever get West Nile Virus, know that it was the boring common mosquito who gave it to you. Malaria, on the other hand, is usually carried by the Anopheles species, which is not common in Europe.

Let’s meet them:

They have different attack strategies. The common mosquito is the one that got crazy at sundown and swarmed Kostas’ garden. It also sneaks into his house and waits for him in the bedroom to approach his ankle the moment it slips out of the blanket.

The tiger mosquito has a larger seasonal variation, and a wider daily schedule. It appears earlier in the afternoon, and would also wait for you at seven in the morning when you’re warming up for a run and take the risky behaviour of staying for two minutes in the same place.

Do you want to make it difficult for mosquitos? The first and foremost recommendation is to remove stagnant water. They can lay eggs almost everywhere there’s a small amount.

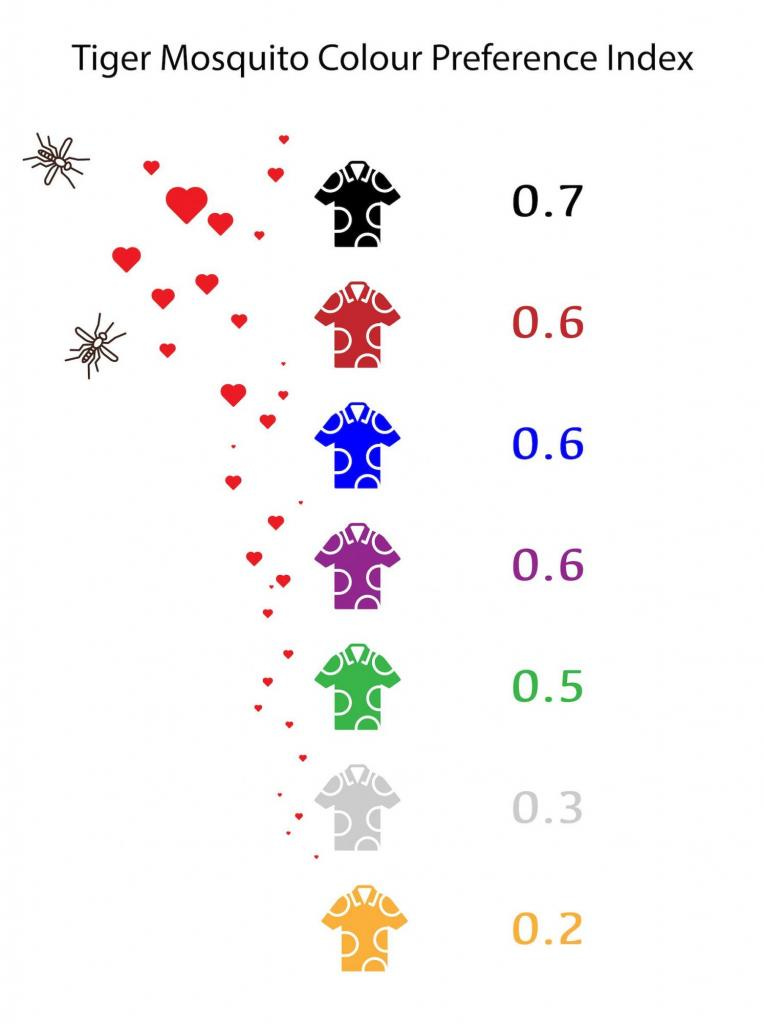

Do you want to avoid attracting mosquitos? Mind your clothes’ colour. They prefer black, and would not be attracted as much to yellow.

Mosquito wants to see the world

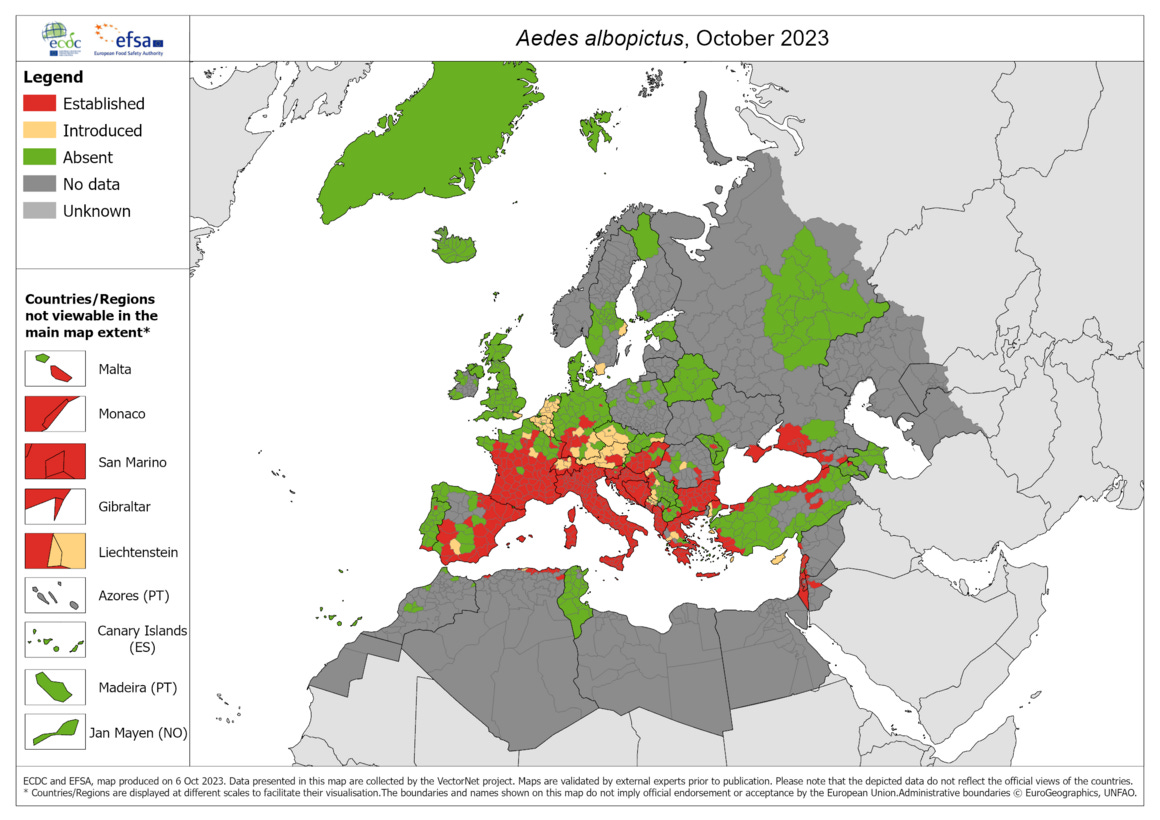

The tiger mosquito is an invasive species. It first appeared in Albania in 1979 and in Italy in 1990.

It came by boat1. The first tiger mosquito recorded in Italy was in the port of Genoa. Most likely, in a shipment of used tyres: water accumulated inside the tyres is irresistible for female mosquitos to lay eggs.

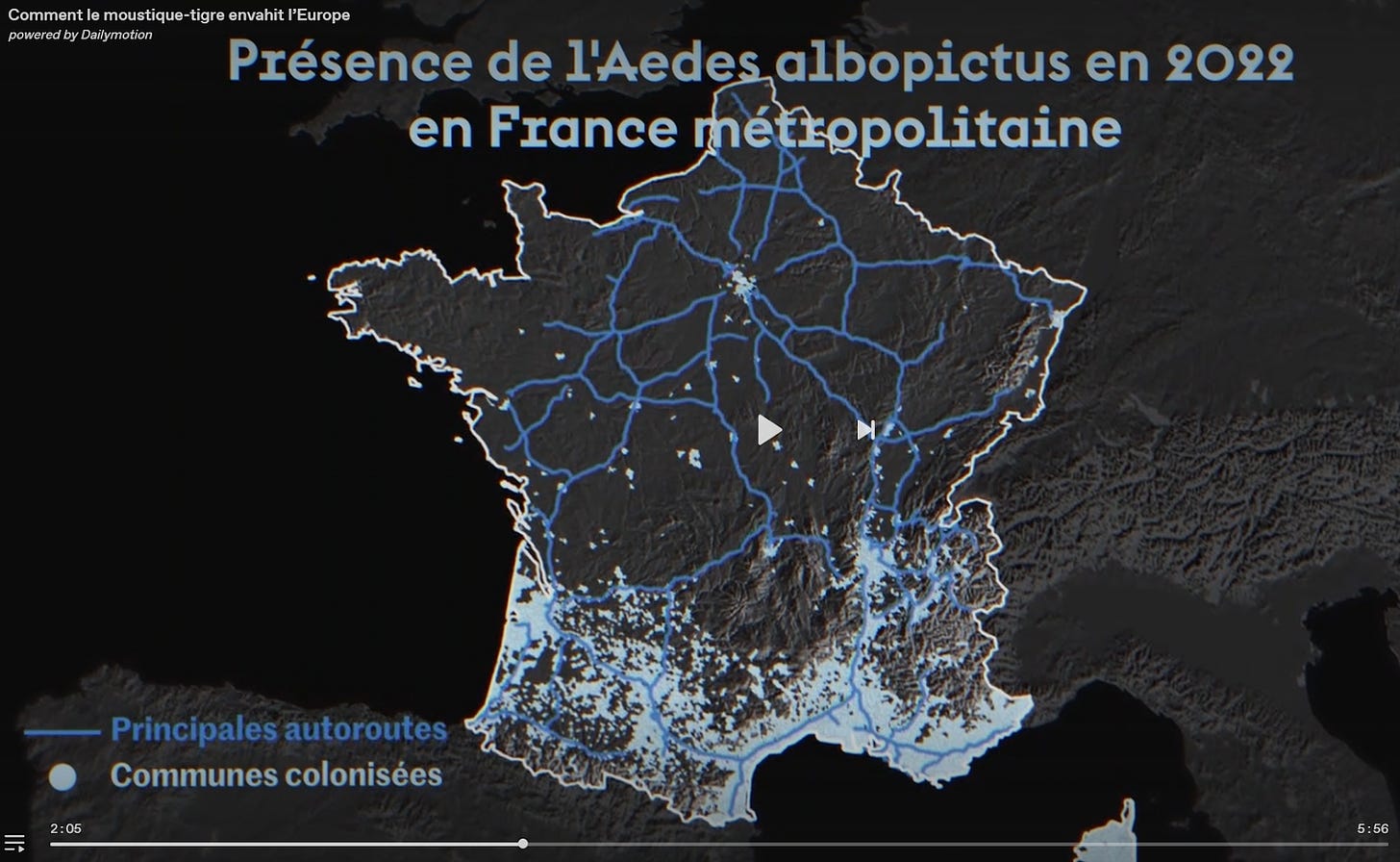

Once ashore, they travel by car. The explanation by Le Monde in this 5-minute video (in French) shows how their expansion follows the road network.

As a result, this is the status of the tiger mosquito conquest of Europe:

But despair, let’s not! As James Bond receives the latest devices from Q to go against the evil forces, we European residents count on a coordinated network of scientists and entrepreneurs tackling mosquitos. Let’s see what they have in store.

What YOU can do to track mosquitos

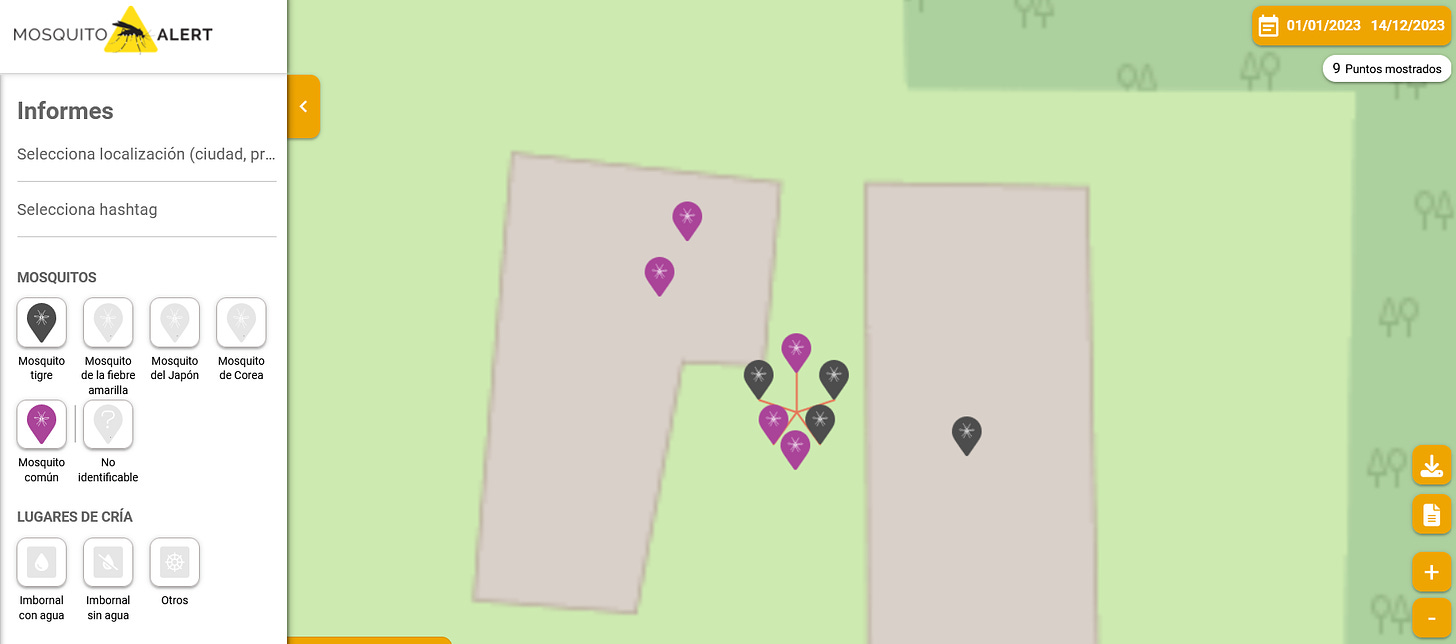

Your contribution as a citizen can help generate a real-time map of mosquito presence in Europe.

Let’s find out the details with Alex Richter-Boix. He’s a biologist at the Spanish National Research Council. With a penchant for science communication, he was until recently in charge of outreach at the citizen’s science project Mosquito Alert.

“With the Mosquito Alert app, you can upload a picture of a mosquito, and it will identify the species and add it to a public map. This is much faster than the traditional surveying method: placing traps in specific places and collecting data weekly. Users of Mosquito Alert are everywhere, and they report at all times.”

An Artificial Intelligence algorithm identifies the species, after having been trained with the thousands of pictures already collected and labelled. Voluntary experts will later review the identification.

Mosquito Alert has been used to detect for the first time the tiger mosquito in some regions. But, once we know it is established, what is it useful for?

“It provides a real-time map of the mosquito activity. We expect that in the future, public administrations will use it to trigger early health warnings. Within the EU-project E4Warning we are developing an early warning system in this way:

First, overlay the climate variables with the vector data to understand the climate-vector relationship;

From that, later, you can estimate if the season will have more or less mosquitos from weather forecast.

Then, insert travel data from places where tropical diseases are endemic - these travellers are the ones that will trigger the outbreak. Now, you have a tool to assess the health risk.”

So, we can track the tiger mosquito, but can we go further? Can we eradicate them?

“I don’t think we can. Even if you clear a certain area, it will soon re-invade it from the surroundings. The goal should not be eradication, but keeping the population below a certain threshold, both for health and comfort reasons.”

Nowadays, Richter-Boix’s activity is focused on European scientific projects. So, we asked him about money.

“Research on diseases carried by mosquitos is relatively well funded at the moment, through several European projects - like INOVEC, mentioned earlier, IDAlert, DURABLE or E4Warning. Also, talking about epidemics in public is not any more a taboo. Before COVID, public administrators did not talk openly about how to prepare for the next outbreak. Policy-makers are aware of the problem, I’m sure of that.”

A different story is the fight on the ground, which can still be improved. Several companies participate in research projects, to fine-tune their traps. It is expected that these traps will be increasingly used in the coming years, because we might need to get used to tropical diseases.

“We’re going to see outbreaks of Dengue and Chikungunya in Europe, because the vector (the mosquito) is already established, and every year the virus arrives through travellers. The risk exists, in the last years we observed a rise in locally transmitted instances of dengue in Southern Europe, and because many individuals are asymptomatic, the actual incidence of dengue could be higher than reported. Local transmission in Europe is not, any more, a surprise. I think I’m realistic when I say that we need to get used to have sporadic and seasonal local transmission cases in Europe and enhance our response.”

What’s next

Kostas and Elena, dressed in white and yellow, have made a tour of the garden, removing all small accumulations of water. They have also asked their neighbours to do the same.

Their friends come again. They show them the Mosquito Alert app, where they have been reporting their catches (and also, their bites!).

This is good, but not enough. The little beasts are still around. What else can be done?

In the next article, we will find out:

The tiger mosquito is not established everywhere in Europe, yet. How are the central European countries preparing for its arrival?

There are scientists collaborating to research mosquito-born diseases. What are their projects about?

How do mosquito traps work? What’s their role in fighting mosquitos?

What does the sterile male have to do with all this?

Stay with us to find out.