Schedules, costs and risks of new nuclear megaprojects in Europe

3/3. Building a new nuclear plant is a megaproject. And, surprise, removing it too.

The nuclear debate resurfaces in Europe

War sanctions against Russia are in full swing1, including an unprecedented effort to cut down on gas and oil. Europe needs alternatives, and a nuclear renaissance is considered2. It comes in two flavours: extending life of existing plants, or building new ones.

We will focus on new nuclear power plants. We’ll target the project management side: schedules, costs, and risks, building on our previous chapter:

How long does it take to build a nuclear reactor?

The World Nuclear Association reports yearly on the number of new reactors connected to the grid. This is the "median construction time for nuclear reactors worldwide":

In 2021, 6 new reactors went online, with a median construction time of 7.3 years. Is this figure valid for Europe?

Three outliers

Three plants under construction in Europe have a bad rep: Hinkley Point C (UK), Flamanville (France) and Olkiluoto 3 (Finland). They're regular anti-nuclear ammunition due to their cost overruns (from 8 to 16 billion €) and delays (from 4 to 12 years). The pro-nuclear camp considers these “outliers”, as they deviate from the construction time presented above.

One nuclear Babel tower

Olkiluoto 3, to be connected in December 2022, was awarded in a fixed-price contract. This means that cost deviations fell on the contractor, the French company AREVA. On a 3 billion € contract, not only they did not make any profit, but lost 8 billion.

🙄

AREVA was bailed out by the French state. The French taxpayer ended up paying for the cost overrun.

What happened at Olkiluoto? We look at the work of Inkeri Ruuska, an expert in large project governance, management and leadership. She holds a PhD, and has worked in her native Finland, Sweden and the US.

Ruuska and her team investigated Olkiluoto 3 as early as 20093, when it was already clear that it was derailing. Some of the problems they identified were:

Coordination between workers of different nationalities and languages. E.g. “There were a lot of Polish workmen, while the supervision of work was conducted by the French, Germans and Finns.“

Finnish companies were expecting to be subcontracted, but AREVA chose mostly French firms.

The lowest bid was selected instead of the higher quality one.

Special requirements for nuclear power plant building were not emphasised in the call for tenders.

For Ruuska, the key element for success is distance among actors. She identified three groups of problems: actors, relationship between them, and project practices, and explained how they increased distance and contributed to the project failure.

Two other projects under construction

There are other reactors under construction in Europe: Mochovce 3 and 4 (Slovakia), and Ostrovets 1 and 2 (Belarus).

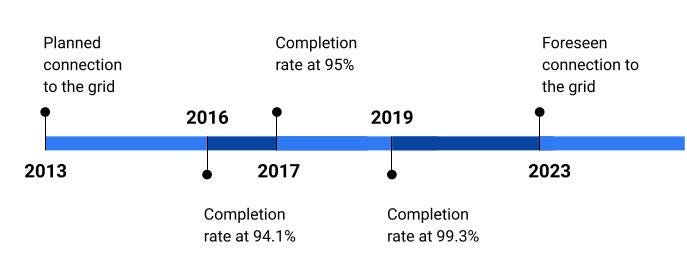

Work in Mochovce 3 originally started in 1987, stopped in 1992, and restarted in 2008 to complete the old Russian designs. These are the official figures of the building progress:

This adds to 20 years of construction work, with 10 years delay from the latest estimation. Cost has duplicated, from the original estimate of 2.8 billion €, to 6.2 billion €, becoming the most expensive construction project in the history of the country.

Ostrovets (Belarus) has two reactors: one connected in 2021, and another one finalised and undergoing tests. It was built by Rosatom, a Russian state-owned firm, in a turnkey contract. The original budget was 10 billion €, which were loaned by Russia, and the original estimation was 5 years. In the end, the first reactor went live with 2 years of delay, and 14 billion € extra cost.

Lithuania is opposed to the project: the plant is just 60 km away from its capital, Vilnius, and the river Neris, used to cool the plant, is from where the city takes 80% of its drinking water. When Ostrovets went online, Lithuania stopped all power exchanges with Belarus, deeming the plant unsafe and a threat to their national security. However, the European Nuclear Safety Regulators Group inspected the plant satisfactorily in 2017.

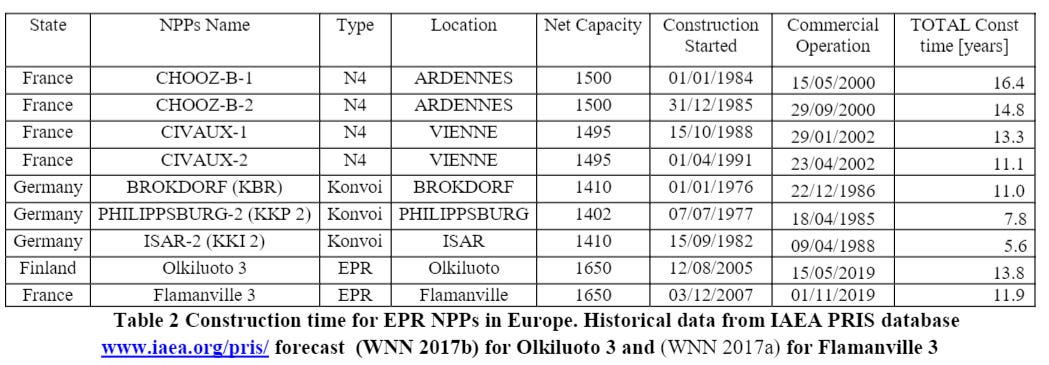

Six reactors completed since 2000

The six reactors that went online since 2000 share a similar story. Located in Eastern Europe, they were started in the 80’s, stopped some years after for various reasons, and then eventually restarted and finished. Here’s a summary:

Up to this point, none of the thirteen nuclear reactors completed or foreseen since 2000 has been on time or on budget.

Two slow starts

Two countries have political willingness to run nuclear but their plans take long.

Poland's electricity depends a lot on coal. For years, they have been doing preparatory work to embark on nuclear power. This is a summarised timeline:

The first Polish nuclear reactor would go live 28 years after the decision to transition immediately to nuclear, which indicates how challenging such a move is. The project would cost 16 billion €. That is, if Everything Goes According to Plan.

Czech Republic runs two plants. Dukovany has four soviet-era reactors put in operation in the 80’s, and Temelin two more modern ones started up in 2000. Building new reactors has been planned in the country's energy policy since 2004. This is their timeline:

The tender to construct 2 new reactors at Temelin failed in 2015 because the Czech electrical company wanted have a guaranteed price in the long term, but the government rejected it. This agreement, however, was reached in 2020, opening up the way for new reactors at Dukovany. The first nuclear reactor in the Czech Republic is expected 32 years after the first political decision to build it.

Eight stopped projects

These are not included in the statistics, as they have been cancelled. Each of them has its own small story.

Hanhikivi, Finland was cancelled due to the Russian invasion of Ukraine. It was originally planned to be connected in 2024, but accumulated 10 years of delay. Finnish Prime Minister, Sanna Marin, announced in February ‘22 that the security risks of building a Russian-design reactor, of which Rosatom owned a 34% stake, were being re-evaluated. In May, the contract was cancelled. Rosatom didn't agree: there's a court case open in which each party demands 3 billion € from the other one.

Still in Finland, Olkiluoto 4 was a victim of Olkiluoto 3. In 2015, the delays in the third reactor triggered the cancellation of the fourth.

Turkey lost two battles against megaprojects. Sinop was to be built in cooperation with France and Japan with a 22.6 billion € budget. 5 years after the deal was signed, the costs had doubled, and the project was abandoned. İğneada, which was to be built in cooperation by China and the US, was also stopped.

In Lithuania, the Visaginas plant suffered a slow motion crash. Planned in the 2010's, it lost momentum after a non-binding referendum, in which more than 60% of the population opposed the construction of the plant. In 2016 the government delayed the project indefinitely until it became cost effective under market conditions.

Russia had responded to Visaginas with the Kaliningrad plant in the exclave neighbouring Lithuania. This project stopped in 2013. Apart from the geopolitical angle, there was no need for such plant in the area.

Bulgaria shot itself in the foot bargaining with Rosatom. The new plant in Belene, started in 2008, was "the largest industrial project in Bulgaria in the last 18 years". But 4 years later, the government insisted on lowering the price of the plant below 5 billion €. This didn't work out, and as a consequence the project was stopped. Bulgaria had to pay 620 million € in compensation.

For Slovakia, the maths were not adding up. It announced in 2008 a new reactor at Bohunice, expecting to have it operational by 2025, for 3.3 billion €. Rosatom required a guaranteed electricity price, to which the government refused. The project then stalled, and in 2019, following a policy revision, it was formally postponed.

Cancellations happen, worldwide. 1 of every 8 nuclear projects between 1970 and 2021 never saw the light4. In Europe the rate seems to be a bit higher between 2000 and 2022. In this article we count 8 cancelled reactors, 6 finished, and 13 ongoing: a 30% cancellation rate.

Two Russian Trojan horses

Akkuyu’s plant is under construction in Turkey since 2018. The first of four reactors built by Rosatom is expected to go live in 2023. The budget is 20 billion €. This project is strongly supported by both the Turkish and the Russian governments, being labelled in the plant’s website as “the biggest project in the history of Russian-Turkish relations”.

Although the plant is in Turkey, it will be fully owned by Russia. In technical terms, its management model is “Build-Own-Operate”. This means that the contractor builds, operates, and also owns the infrastructure. Rosatom is responsible for all capital expenses, takes care of the fuel and the waste, and will continue to do so for the life of the reactor. This means 60 years of pictures like this:

The risks of the plant at Akkuyu have been studied by Ioannis Gregoriadis. He is a Greek scholar teaching in a Turkish university. His studies cover Law (undergrad), International Affairs (masters), and Politics (PhD). He is a prolific and well-cited researcher, an one of the experts in the Hellenic Foundation for European and Foreign Policy, one of the most relevant think tanks in Greece.

Grigoriadis focuses on the asymmetries of the relationship between Russia and Turkey, and in the risks of the construction of the plant5.

Funding. In this model, the contractor pays for construction costs. Can Russia keep on investing in it, instead of diverting funds for the war? Grigoriadis believes Russia will push on despite the economic aspects, because something else is at play: to maintain leverage over Turkey. We would also add the case of Ostrovets in Belarus, where the apparent loss of 14 billion € didn’t impede the project.

Delivery dates. Can Turkey open the first reactor in 2023, to celebrate the 100th anniversary of the founding of modern Turkey? In August 2022, an apparent failure to meet deadlines triggered Rosatom to cancel contracts with Turkish suppliers and sign new ones with Russian counterparts. Here lies a related problem, which we have already seen in Olkiluoto: the foreign contractor is replacing local partners with foreign ones.

Energy independence. Turkey claims that nuclear will make them more independent. If their original plans had been successful, maybe they would be, with three plants run by three different suppliers: one Franco-Japanese, one American, and one Russian. But the current state of affairs links 10% of their future electricity supply uniquely to Russia.

Environmental aspects. The warming water of the Mediterranean might not be enough to cool the reactor. There are also seismic risks in the area. The last earthquake hit in 2015 with a 5.2 magnitude, but the reactor should be able to resist a magnitude 9 one.

Similar risks affect another a nuclear plant inside the European Union, that of Paks (Hungary). Its four reactors, built 40 years ago, produce 40% of the country’s electricity. Another 32% is imported, and to reduce that figure, two more reactors will be added. To achieve this, Hungary partnered with Russia. Due to their role as suppliers of nuclear fuel, Rosatom is not included in the EU sanctions. As for Akkuyu, the following aspects are also relevant for Paks:

Intergovernmental collaboration: regular meetings between Orban and Putin.

Financing: of the 12.5 billion € budget, 10 are loaned by Russia. The project has been awarded as a fixed-price contract, so all cost overruns are to be born by the contractor.

The project accumulates 5 years of delay at the moment. However, it has recently been cleared to start construction.

Paks has another dagger hanging onto it: a case in the European Court of Justice. Hungary awarded the project without a public tender. Subsequently, this was investigated by the European Commission, as it could be an illegal use of state aid, but in 2017 it cleared the project. Austria disagreed and appealed to the court in 2018, and the case is currently undecided. Should the decision be overturned, construction at Paks would stop.

Austria could be labelled the most anti-nuclear EU country. Nuclear is banned there since 1978. Leonore Gewessler, Ministry of Climate Action since 2020, and member of the Green Party, represents the country’s anti-nuclear stance. She criticised Mochovce 3, in Slovakia, the plans to build Krsko in Slovenia, and leads another court case against the labelling of nuclear power as “green”.

Three decommissioning projects

In the coming years many of the nuclear power plants built in the 80's will reach their end of life, at 30-40 years. We now face a new type of megaproject: nuclear decommissioning.

There are two options for decommissioning: immediate, and safe enclosure

"Immediate" projects can start right after the reactors are shut down. These projects can take up to 27 years (as it's estimated for Loviisa, Finland). In "safe enclosure" ones the plant needs to be fully isolated for a period of time, ranging from 20 to 70 years.

The 2002 report by the International Atomic Energy Agency6 is optimistic about safe enclosure:

"It is considered that after the period of 20 to 70 years of safe enclosure, a lot of experience and practice will have been acquired, technologies and tools will be more mature and reliable, and most of them would be commercially available."

Following this, we will label safe enclosure as the "Futurama approach for nuclear waste management".

There are three decommissioning projects in Europe.

One condition for Slovakia, Lithuania and Bulgaria to join the EU was the shutdown of their unsafe and not upgradeable nuclear power plants.

This was a huge challenge for Lithuania, as the nuclear power plant at Ignalina produced 70% of the country's electricity when it was decommissioned. Today, Lithuania imports electricity heavily from Sweden.

These projects are funded by the European Commission and the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development. These are the costs associated7:

Bohunice, Slovakia. 1.3 billion €, two soviet-era reactors, to be completed in 2025.

Kozloduy, Bulgaria. 1.4 billion €, similar setup.

Ignalina, Lithuania. 3.3 billion € to dismantle a large graphite core reactor (same type as the Chernobyl one).

From what we have researched, costs and schedules for these projects seem accurate. A large-scale study from the OECD in this area in 2016 with a detailed case study for Bohunice estimates its costs at 1.14 billion €, relatively similar to the actual ones. The EU funding and associated political follow-up seem to have introduced strict requirements for project management.

In nuclear decommissioning, good project management approaches are still a big challenge. The OECD report on the topic8 mentions that:

There is no universally accepted standard for decommissioning cost estimates. This makes comparisons difficult and reduces transparency and confidence.

Not all countries include the same chapters in the decommissioning plans. For instance, "on-site storage of radioactive waste" is included in the Slovak Republic plans, but not by anyone else.

Uncertainties are managed very differently across countries. Finland includes a 10% budget for contingencies. Switzerland 30%, by law. The UK, arguably the most advanced, runs computational models based on Monte Carlo simulations with input from previous projects.

We'll close the decommissioning chapter precisely in the UK. Their Calder Hall power plant closed in 2003 after 47 years of operation. The UK's Nuclear Decommissioning Authority estimated, in 2009, that the cost would be around 28 billion €. 10 years later, the new estimate is 141 billion €. This is 4-5 times as much as it costs to build a new one. The final site clearance at Calder Hall is planned to be finished in the year 2120.

Three academic opinions: is Flamanville an outlier?

We’re getting to the end. Let’s look back into the question that opened this article, and explore what the academics have to say.

Benjamin Sovacool is a Professor of Energy Policy at the University of Sussex. His research work covers the politics of large-scale energy infrastructure. He's also an author of the IPCC reports and an adviser on Energy to the European Commission.

In 2014 he published an analysis of 401 power plants in 57 countries9, looking for cost overruns. 180 of these were nuclear. He found that:

Nuclear reactors had a mean cost escalation of 117.3%

64% had a time overrun

97.2% had a cost overrun

What are the reasons for this? Sovacool proposes three ideas:

These projects have multiple factors and actors, where things can go wrong. This reminds us of Ruuska’s work in Olkiluoto 3.

Poor management is a factor. Outsourced projects have poorer performance than internal ones.

Sometimes the cost overrun is intentional: politicians might want to conceal the real cost of a project by sponsoring a lower cost estimate. We have heard this as well from Flyvbjerg in the previous chapter.

Giorgio Locatelli is Full Professor of Complex Project Business at the Politecnico di Milano University. He researches project management and complex projects, and has expertise on the nuclear sector.

In his article from 201810 Locatelli picks apart the complexity layers of a nuclear power plant.

Technical: it's not only nuclear engineering involved, but also civil, electrical, mechanical, hydraulic, materials, and IT.

Organisational: nuclear plants have very strict and unique regulations and are a sensitive political topic.

Financial: the investment required is huge, and revenue generation only comes when the work is fully finalised, several years after start.

Locatelli acknowledges that "all nuclear power plants under construction in Europe and USA are delivered over budget and late". He doesn't blame technology though, and puts the South Korean example as a counterfactual. South Korean nuclear plants are delivered on time and within budget. Locatelli points at standardisation as the key. 12 of the 25 active reactors in Korea are the same model, and the 3 currently under construction are an evolution of it. The project delivery chain is also standardised: the same stakeholders are involved every time.

Locatelli also applies "reference class forecasting" to Flamanville and Olkiluoto. He compares them to previous similar plants, and is able to ascertain that the current costs and budget are to be expected. The planners however demonstrated an optimism bias when estimating, and this is what led to the current deviations of the plan.

We close the academic round with Bent Flyvbjerg, who has its own stance on nuclear power. In his opinion:

In 2016, Flyvbjerg opposed the construction of Hinkley Point C11, arguing that it was too big, too fragile. Instead, he proposed investing in many smaller and modular projects, which can go online quicker.

“For big nuclear power, the cumulative threat of fragility is exacerbated by the responsibilities of nuclear decommissioning and handling of nuclear waste over time horizons so long that humans have no track record of being able to effectively plan for them.”

One conclusion

The three projects with which we opened the article are not outliers. All nuclear power plants (except those built under the standardised model of South Korea) have cost overruns and go above budget. In Europe in particular there hasn’t been any nuclear construction which has been a project management success. Cost and budget deviations are to be expected of megaprojects, as nuclear reactors are.

Note that the time estimation for most nuclear projects listed in the article has been of 5 years. If there’s a single idea that the reader should keep from this series, is that the next time someone comes with a nuclear power plant proposal that takes 5 years and costs 3 billion €, we can quickly call this proposal for what it really is.

The involvement of Russia, which is willing to lose tons of money in exchange of keeping leverage on other countries, makes the nuclear endeavour even more risky, all the more in the current war.

There is, however, a silver lining for nuclear proponents. It starts with standardisation, South Korea style. It follows by having the same companies involved once and again. It might still not work, due to the mature anti nuclear movement in Europe. But if only, if only there was a European body to coordinate nuclear actions, that could be leveraged to make nuclear collective investment, and not an individual national endeavour.

Up to now the EU has adopted 8 sanction packages against Russia. Full details by the European Commission: Sanctions adopted following Russia’s military aggression against Ukraine.