In the previous chapter, Kostas and Elena had killed 47 mosquitos on a nice summer evening. Now, they have started to report their catches through the Mosquito Alert app. But that’s not enough, they want revenge.

They’re not the only ones. There are several other mosquito fighters throughout Europe. Some are preparing for the arrival of the tiger mosquito in Central Europe, some are researching new techniques in urban environments, some others are developing traps and employing them further South. One of them is running projects in two tropical islands that haven’t seen a mosquito in months. And we will finally meet the sterile male insect that gives name to this series.

Let’s start: how can a country like Belgium prepare for the arrival of the tiger mosquito? To find out, travel back in time with me to July 2018.

The Mosquito Maginot Line

We’re at Milan Malpensa airport, about to board a flight to Brussels. The plane is on the tarmac, people are boarding through the stairs, the sun is just setting. As we are two meters tall (stay with me on this one), while we locate our seat, we can see the ceiling of the cabin. It’s full of mosquitos, there are easily a hundred. We can barely control our desire to make a scene and start splatting them all over. Instead, we channel our rage sending a tweet to Ryanair. Then, lights are dimmed, and mosquitos can have dinner while the plane takes off.

In flights to and from countries where Yellow Fever is endemic, the crew sprays the whole cabin with insecticide right after doors are closed. They know what they’re doing, and it doesn’t include giving a free ride to any disease-carrying mosquito.

This spraying must be requested by the destination airport, something that Brussels International is not doing. Belgium, however, is well-prepared to deal with tropical diseases, due to its colonial past. The Institute of Tropical Medicine, in Antwerp, was created by King Leopold II, also known as the personal owner of the Congo Free State (he called it “free”, King of the Irony).

Belgium also relies on a citizen mosquito surveillance system . Thanks to this initiative, it was known that the black-and-white beast had survived the 2023 winter. For the first time, it is established in Belgium, and researchers are not surprised.

Well, it’s not that the Maginot line was very successful either to prevent the Nazi invasion in World War II. In general, operational efforts on the ground can be improved throughout Europe. The good news is that the supporting scientific work is going well.

The European network of mosquito researchers

Researchers are so used to cooperate across borders that we could say they have a built-in European Perspective. In our previous article, Alex Richter-Boix mentioned up to four active scientific projects to fight diseases transmitted by mosquitos. Let’s take INOVEC, for instance. There, we can find scientists belonging to 21 organisations, from 13 countries, from Universities, research centres, and private companies.

One research project that finished in 2023 that had a big impact was “AIM-COST”. AIM stands for Aedes Invasive Mosquitos. The project coordinator was Alessandra della Torre, one of the lead European researchers on the tiger mosquito.

The goal of the AIM-COST project was to move from just sampling mosquitos to having complete models and maps. This is how they word it:

“We need to know where they are and anticipate where they will be and how prolific they will be. We set out a roadmap comprising surveillance, modelling, data visualisation and mapping.”

Scientific work will light the road. But, per se, it will not rid us of mosquitos.

“We aim to inform control but not to cover specific control methods or strategies.”

So, how do we get the operational part going?

Let’s start with a basic approach. Mosquitos are mostly attracted by the CO₂ that humans breathe out. That’s how they locate us. Then, they gradually switch to follow our body smell. That’s how they bite us.

Knowing that, couldn’t we set a trap?

Biogents - Traps to fight the infestation

20 years ago, scientific mosquito traps mostly used carbon dioxide from dry ice as attractant. Other models produced it from burning propane gas. But those scientists who wanted to study the yellow fever (or dengue) mosquitos especially struggled to capture even a handful of them.

Then, entomologist Martin Geier, his colleague Andreas Rose and others at the University of Regensburg entered the scene, designing better traps. They started to research attractants, and first tested them on yellow fever mosquitos that they would rear.

“Rearing yellow fever mosquitos is actually quite easy. They lay many eggs, and these eggs can be stored for months. You just add some water, and in a week and a half you have mosquitos.”

Geier and Rose then founded Biogents AG, a company specialised in mosquito traps. Today, their BG-SENTINEL is the standard trap that every mosquito research team will use to capture yellow fever mosquitos and many other species.

Very early, they realised that there was a consumer market as well: people like our protagonist. But Kostas will not be happy just catching some mosquitos for sampling, he wants to get his garden rid of them. Is this realistic?

“It is. It’s possible to set a perimeter of traps. It has been done both in small and large set-ups.”

Rose points to a luxury tropical island in the Maldives (we’ll get there later in this article). They are serious about protecting tourists from mosquitos. At some moment, they used so much insecticide, that almost every insect on the island was killed, and local fruit and vegetable gardens faltered due to the lack of pollinators. That’s when they switched to traps. They managed both to eradicate common and tiger mosquitos, and to bring back the other insects, spending less than with insecticides.

What are these traps about? There are two types: passive and active.

The passive ones are called “ovitraps”. They lure the female with stagnant water so that she tries to lay eggs there, and then gets trapped by sticky paper.

The active ones contain a small envelope that smells like your sweaty clothes after a run. You can also attach a CO₂ bottle to it.

“But if you just place the smelly envelope on the table, mosquitos will not come. You need to simulate real conditions. The sense of odour of mosquitos is so refined, they can analyse the 3-dimensional shape of an odour plume.”

Spraying insecticide is easier, whereas it takes some knowledge to find the right place to set up a trap. To start with, it must be upwind. The wind blows, it hits the smelly envelope and the CO₂, and creates a plume very similar to that produced by a human, that the mosquito will follow.

How is Biogents testing this? Initially, with a wind tunnel. They set up the attractant in the upwind direction, then switched on different air currents, and saw how mosquitos reacted. These findings were used in the development of trap prototypes that were then tested in the real world.

The trap itself does not look high-tech: a smell cocktail, a ventilator, two nets, and a hard plastic container. We asked Rose about their product development strategy.

“First, we want to reduce the use of plastics, both in the traps and in the packaging. We also work on making our products even more efficient.

Then, we want to identify mosquitos of special interest, like disease vectors or invasive species. Our BG-COUNTER is already able to count trapped mosquitos, and report every 15 minutes. This gives us real-time monitoring, which is essential for an efficient mosquito control. Add the weather models and the population forecasts, and we have a very good tool also produce predictions and improve the efficiency even further.

We also have more open research activities, like the development of electrified window blinds that repel mosquitos via the current field, which started as a cooperation with the Institute for Global Health (ISGlobal) and other partners.”

You can follow Biogents AG in LinkedIn. They currently employ 40 people, 1/3 of which in Research and Development activities.

Later on we will see a practical use of traps. Now, let’s switch to a counterintuitive approach to reduce the mosquito population: by adding more mosquitos.

Fighting mosquitos with good mosquitos

Throughout last summer, 5 million mosquitos were released in the neighbourhood of Casteldebole (Bologna). They were all sterile males reared in the lab. They mated with tiger mosquito females, which therefore couldn’t produce any offspring. This was a pilot project of the “Sterile Insect Technique”, and the population of tiger mosquito fell by 60%.

The company behind is Centro Agricoltura Ambiente “G.Nicoli” (acting as an IAEA - International Atomic Energy Agency - collaborating centre). They have been fine-tuning the technique in the last years. We talked with Romeo Bellini, the senior entomologist in charge of their Research and Development work.

“The current available technology is not enough to control the tiger mosquito. That’s why we are developing the sterile male technique. It’s not new, it has been applied to other insects. We want to make it operational and commercially viable to combat the tiger mosquito. Besides, it doesn’t have any environmental or health impact.”

In 2007, there was an outbreak of Chikungunya in Emilia Romagna. It triggered a strong reaction, and it might be the reason why this area is among the most advanced in Europe combatting mosquitos, with good coordination between the regional health system (in charge of the public health surveillance) and the cities (in charge of disinfestation). Their active surveillance network detected West Nile Virus in mosquitos and birds in summer 2023, and preventive measures were launched following their Control Plan.

Bellini reminds us that the 2007 Chikungunya outbreak was long ago.

“There are higher priorities at the moment, and public interest and investment have faded. However, people are still spending their own money. Following a socio-economic survey conducted by the “LIFE Conops” project a few years ago, in Emilia Romagna, families spend €60 million every year in anti-mosquito products, versus €5 million of public money used to fund the anti-mosquito actions.”

The tiger mosquito expands very easily because it breeds in small quantities of water, where a single female can lay hundreds of eggs. To complicate the disinfestation work, most of the breed containers are in private properties. It’s not enough to apply insecticide.

“We are still small. We can produce 1 million mosquitos per week, and we are planning to increase the production capacity. We are also developing models that consider the weather variation to figure out the optimal number of mosquitos to release.”

CAA will run again the project next year, with several goals: reduce the cost, increase the efficiency of the delivery using drones, and reach an 80% reduction of the population. CAA might be able to offer their services to the municipalities in the region 5 years from now.

Some potential clients for the sterile male could be their neighbours, the Swiss.

Southern Switzerland pushes ahead

Kostas and Elena cross the nearby border to Switzerland from time to time. When they do, and it’s summer, it seems there are fewer mosquitos. How is that possible? The environmental and urban conditions of the towns north and south from the border are very similar (even the language is the same, not that this is relevant for mosquitos). What is happening at the customs check?

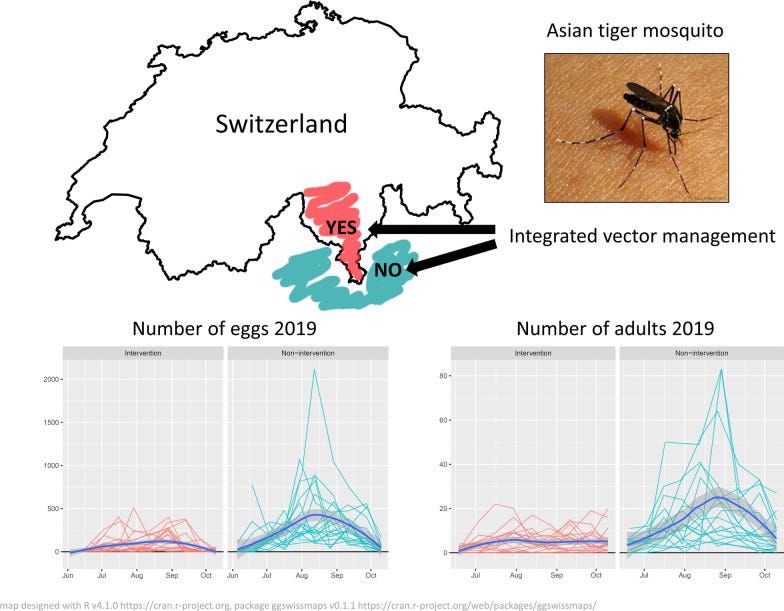

Let’s find out with the help of the published work of the researchers at the University of Applied Sciences and Arts of Southern Switzerland (SUPSI)1.

We learn that the tiger mosquito arrived in Southern Switzerland in 2003. We’re not surprised to hear that it was detected for the first time on a highway.

Southern Switzerland hasn’t been able to fence off the mosquito. But, unlike Northern Italy, they have a plan against it, and it’s working. They remove breeding sites (stagnant water) where they can. And where they can’t, they apply larvicide. Standard insecticide to kill adult mosquitos is reserved to combat health outbreaks.

So much is Northern Italy not controlling invasive mosquitos, that it is used by Swiss researchers as the “no intervention” data set, for comparison. This makes Kostas mad. Emilia Romagna, just two hours away, is at the top of the mosquito game, while Lombardy, where they live, is at the bottom.

And the Swiss are not happy either, because mosquitos get reintroduced constantly from Italy (many people commute daily across the border).

Looking at the graphs, it seems it’s possible to reduce the population of tiger mosquitos to 25% using existing methods. Do you want more? Read this:

Results show that these devices reduced the presence of mosquitoes at all developmental stages between 92.6-97.2%

What devices!? What sorcery is this? What high tech are the Swiss using?

It turns out it’s just a piece of plastic.

Mind you, a piece of plastic situated in the right place, which is a sewer drain. Those are mosquito’s favourite breeding places in cities. They’re everywhere, they’re difficult to reach and mantain, they’re humid and accumulate water. A mosquito heaven.

An Italian company decided to create a filter. The Swiss university validated the model. The result: more than 90% of mosquitos, gone2.

Not bad! But we’re holding a wild card since the beginning of this article: the Maldives. Let’s go back there.

The tropical islands that got rid of tiger mosquitos

“It’s true that tropical diseases are circulating again in Southern Europe. But let’s take a history lesson: malaria was eradicated from the Netherlands in 1959, and from Italy in 1962. This is very recent. It’s possible to fight back, but you need to do it thoroughly and go all the way.”

These are the words of Bart Knols, biologist and specialist in mosquito control and elimination. He is in a mission to fight mosquitos in Europe, and beyond. Armed with traps, he has contributed to free two tropical islands from mosquitos, one in Maldives3, and one in Philippines4. He’s showing that it’s possible to counter the invasion with the currently available tools.

He’s a specialist in tropical setups, but we have a geographical bias, so we asked: how can you fight against mosquitos in cities?

“To get maximum impact, we have to integrate the existing tools:

We start establishing a perimeter. The tiger mosquito is lazy, it will not fly further than 200 meters from its breeding site. So let’s start securing a reduced area.

Then, set up several traps. They can help to reduce the amount of mosquitos.

Later, launch the sterile male attack to really stamp down the population.

From here, we iterate. We learn to be more efficient and more cost-effective.”

Knols advocates a stricter approach to private gardens, where stagnant water abounds.

“Explain to the owners: you’re breeding mosquitos. If they continue, fine them, and with the money hire technicians to remove breeding sites”.

Knols is optimistic, with a nuance. We need long-term planning, and election manoeuvres get in the way.

“In the Netherlands, it’s a total mess. We’re losing the battle. We’re not doing enough. Politicians can’t think beyond 4 years, and this problem requires long-term thinking.”

Europe might be a beacon of hope.

“This is a European issue. It should be dealt with in Brussels. But it’s not even on the agenda!”

What about new technology?

“Traps are very good attracting mosquitos, but they have to increase their efficiency at capturing them. The Sterile Male technique is still expensive, in particular the cost of sterilisation. That was the bottleneck I found when I wanted to implement it in the Maldives (and shipping sterile mosquitos from Bologna was not possible, they would die in the trip)”.

There are several individual efforts, and market potential. But that’s not enough to scale. You need appropriate funding and a coordinated approach.

“The ideal mechanism would be a public-private partnership, with the local authority coordinating and contracting mosquito-disinfecting services.”

Who can lead the way, if governments don’t? Probably the hospitality business. This was the case in the Maldives, as they’re very interested in keeping tourists free from mosquitos.

A renewed hope

Kostas and Elena know now that passive traps can capture some mosquitos, and active ones can capture many, if you simulate accurately human odour and breathing.

They are looking at the reduction rates achieved by the different projects: 60% by the Sterile Mosquito pilot, 75% by the Swiss standard controls, 92-97% by the sewer trap, and 100% using Biogents traps in tropical islands.

They’re conscious that the tiger mosquito might be impossible to eradicate, but it seems possible to secure certain areas. They’re hopeful, thinking about the perimeter to set up around their house, or even the whole condominium if the neighbours want to contribute. In the future, they hope that local authorities will step in, hopefully commissioning a Sterile Male Insect project.

They look forward to reclaim their garden, and they feel armed with a load of knowledge, supported by an army of European researchers and practitioners, prepared for what is going to come this summer.

Addressing the spread of invasive mosquito species in Europe is crucial for public health. Implementing surveillance and control measures can help mitigate the risks associated with mosquito-borne diseases. Thank you for highlighting this pressing issue.