The European Perspective on Megaprojects. Part 1 of 3: new stadiums for the EURO 2004 in Portugal

Welcome back to your regular dose of non-institutional European thinking and action! If you haven't done so already, add our pilot issue to your reading list.

Out of the feedback we received on the pilot issue, one comment caught our attention: "It was a bit difficult to read because you were jumping across very different topics". Indeed, in chapter 1 we focused on four European personalities, and we made the themes turn around them, making for a not-so-smooth reading. In this issue we shift gears, and opt to tell a more solid story, weaving the contributions of the European personalities into our narrative.

Today we’ll be looking into Architecture and Football and Project Management. We will meet an architect that was assigned a task, accomplished it according to the specifications, but ended up litigating with his client. We will visit stadiums that once hosted a football European championship and today host fourth-division matches. We will compare the actual cost of the stadiums with their original budget, and we’ll wonder why. Let’s kick off.

Architect Eduardo Soto de Moura and the Municipal Stadium of Braga, Portugal.

Soto de Moura, now 70, has received the Pritzker Prize, one of the most important architecture accolades in the world. Part of the work that earned him this distinction was the Municipal Stadium of Braga. It is carved out of an abandoned quarry, and named thereafter (A Pedreira = The Quarry). It is built in the city where Soto de Moura's father was born, and it was built for the male European Football Championship in 2004, that put Portugal in the focus of world sports. This could have been a story with a happy ending.

Soto de Moura is a functional architect. His work considers the constraints coming both from the terrain and from the intended use of the building. He prides himself on designing and building to solve a specific problem. In several interviews, Soto de Moura has laid down what was requested from him:

UEFA mandated stadiums with at least 30.000 seats

And capable of being fully evacuated in 12 minutes.

It should favour the TV broadcast. In Soto de Moura's words, he realised that he had to build "a theatre".

So, he solved for the requirements and for the space where it was built. And on top of that, he produced an architectural landmark, something that the city could be proud of. A heritage for the local team, which has been using it since its construction. Who wouldn't want to play there?

It turns out that it's precisely the local team, Sporting Clube de Braga, that doesn't want to play there. In 2021 they launched a video promoting the return to their old arena, Estádio Primeiro de Maio.

The Municipal Stadium of Braga doesn't meet the current needs of the S.C. Braga. Maybe the club was not asked at the time, or they only discovered what they really needed after the stadium was built, or maybe they were too optimistic about the use of this infrastructure. But they know what they want now and stated this in 2019 in an assembly1:

A smaller arena (circa 20.000 seats)

In a central area (instead of in the outskirts)

Business-oriented

Adapted to the needs of the club, their supporters and families.

And last but not least, with lower maintenance costs.

Because the current stadium, built 18 years ago, is not yet fully paid. Every year the city needs to dedicate an important part of its budget to cover the interest fees of the loans requested to build it. The original forecasted cost of the stadium was 30 M €. Today, it is acknowledged it can reach 195 M €. On top of this, Soto de Moura has taken the city to court because of delayed payments. The city of Braga claims that the architect must be paid according to the original budget, while the architect claims that the city must pay him according to the actual costs. In 2021 an extrajudicial agreement was reached, by which 5 M € will be paid in monthly instalments to the architect.

What could have been a nice story is now broken into pieces. What went wrong?

In 2000, Portugal embarked on a construction frenzy of football stadiums, in preparation for the Euro 2004.

From 1996 until 2012, the Euro was a 16-team competition. In all other cases (1996, 2000, 2008, 2012), the host countries used 8 stadiums, but Portugal decided to use 10. It was also common to take advantage of the event to renovate and upgrade stadiums, and to build some new ones: 3 new stadiums were built in 2008 and 2012. However, Portugal decided to build 7 new stadiums.

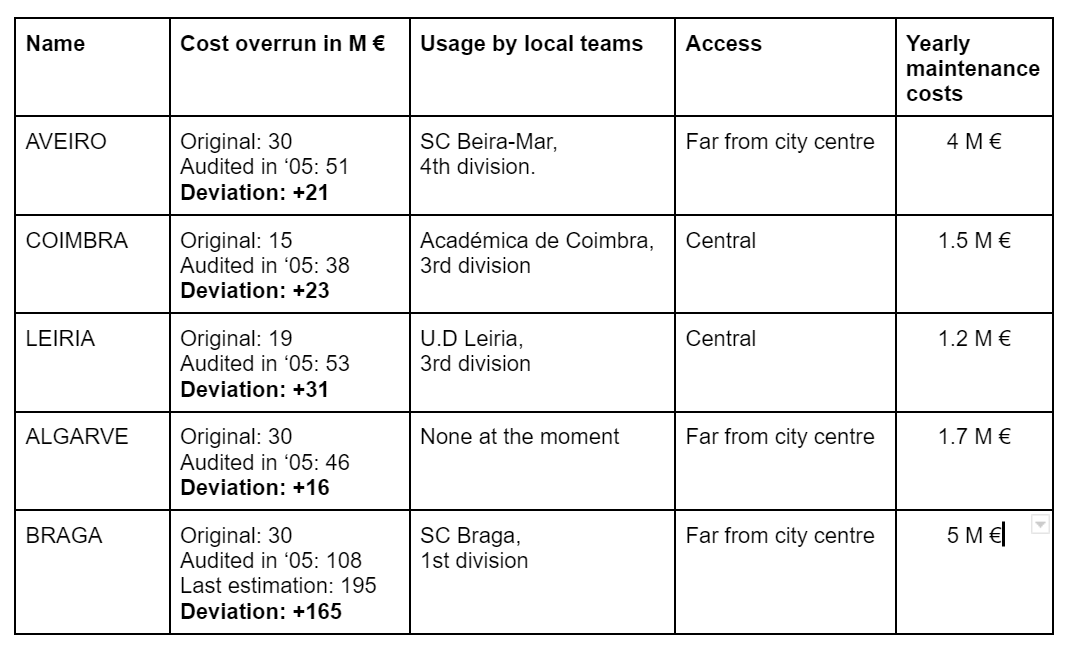

Although they were ready on time for the competition, all of them suffered delays regarding the contractual date. Also, all of them suffered cost overruns.

We can divide these stadiums in two groups according to their use today: those that have found a way to be profitable and are currently used, and those that haven't. In the first group we have for instance the Jose Alvalade stadium in Lisbon. It's home to one of the biggest local teams, Sporting Clube de Portugal. It is ranked as a 4-star stadium by UEFA, and it's at the centre of a complex that includes a mall, cinemas and offices. Its acoustics were specifically engineered to host major concerts. It's used regularly by Portugal's national team.

The others are problematic. They're not profitable, local teams don't want to play there, and the attendance is well below the capacity. Some notable critics have suggested that if they're not profitable, they should be demolished2.

Portugal has recently embarked on a new project to host the 2030 World Cup (together with Spain and Ukraine). To the surprise of none, the 3 stadiums that are proposed are among the non-problematic ones.

In search of the public good

The cost overruns were audited by the Portuguese Court of Auditors in 20053. They highlight the lack of consultation from the public administrations to the local clubs, who were going to be the natural heirs of the stadiums.

Now, let’s look at the response that the Leiria municipality gave to the report. They claim that it's up to the local government, and not to the sports club, to decide about the stadium. In their opinion, football clubs are private entities, while the local government is the legitimate representative of the local civil society. They acknowledge the cost overruns, and the changes done to increase the scope of the original project. However, interpreting the "voice of the people", the Leiria municipality claims pride in having built a modern stadium, functional not only for football but for other Olympic sports.

Fast forward to 2011. The municipal stadium of Leiria has failed to be profitable. Due to missed payments of a national tax, it has been seized by the Portuguese tax authority. The municipality has put the stadium on sale for 63 M €, but no buyer was interested.

There were other options

There were several options to reduce the number of stadiums used.

Lisbon and Porto had two stadiums rebuilt each. It could have been an option to do only one per city, and get the main clubs to agree on sharing it. This model is common in Italy, where two clubs share the stadium in Milan, Rome, Genoa and Verona. But this would have been met with strong resistance from football fans.

Braga and Guimaraes are just 25 km away, so one of the two stadiums could have been saved. But choosing one over the other would have been difficult considering the traditional local rivalry.

The Algarve Stadium, built in the middle of nowhere, could have easily been spared. But then, Southern Portugal could have felt discriminated against compared with the Northern part.

In the end, considerations foreign to sport resulted in extra spending, which turned into financial liabilities, and now everyone is worse off.

An introduction to megaprojects

Megaprojects is the research topic of Danish economic geographer Bent Flyvbjerg. He has studied the poor performance record of megaprojects and the reasons behind. Looking at this work, we will be able to understand why the EURO 2004 construction frenzy in Portugal went sideways.

Why did the delays and cost overruns in the EURO 2004 stadiums happen? What went wrong and how can it be prevented?

Subscribe now to find out in part 2 of this series.

Great piece and much needed analysis, deserving reflection. I wish some lessons would be learnt