The story of the Erasmus friends' reunion in which they travelled by train

And the issues they found along the way

The city is Antwerp. It's around 23h, on a nice, warm Friday night in the middle of May. A group of Erasmus students riding their bikes are crossing the pedestrian tunnel under the river Schelde. They have just stopped by the Night Shop, and now their bike bags are full of cheap beer. They arrive at the neighbourhood of "Linkeroever" (which means, literally, "left bank") and stop at a place where they can enjoy the particular skyline of Antwerp: the cathedral, the bank, and the police headquarters. "A symbol of the factual powers in the city", they say, maybe for the hundredth time.

This might be their last opportunity to party together. Soon they will finish their academic year and return home. They avoid the topic at first, but inevitably someone mentions it. Then, they become emotional and start to remember the moments when they met, the first parties together when it was still cold. They're still surprised at how quickly they formed a group with people from many different nationalities. In the group that is drinking together today, we have students from Spain, Belgium, Greece, Latvia, Scotland, Italy, Romania and Sweden. Most of them met already in the newcomers' sessions organised by the University of Antwerp.

After several beers, it becomes evident that they are the best friends they ever had and the best they will ever have. They have committed to keep their Signal group running forever (even those who favour Snapchat have agreed to this). They will never forget each other.

Suddenly someone launches a big proposal: what if they meet again next year?

An Erasmus reunion

- Yes! Let's meet again here in Antwerp!

- Or somewhere else in central Europe!

- But will we have money for this? I will not have finished my studies by then!

- Should we take the plane? Would there be a way to make the trip more sustainable?

- We should travel by train! That would be an adventure!

As they keep on drinking the idea becomes more and more clear: they will travel by train. It doesn't matter if they come from different corners of Europe, they should find a way to reach a central point in less than 36 hours of travel, spending one night onboard. Maybe they can reach Berlin, maybe even Brussels and then Antwerp!

They settle on the date: early June next year. They celebrate until they run out of beer. They ride their bikes home across the streets of Antwerp, the pavement full of tram lines. For the last time, they race each other through the empty streets, trying to avoid their bike tires getting stuck in the middle of the tram track.

The day after

The day after passes by discreetly. After all, the sun was just rising when they reached their homes, so most of the time, they just slept.

Two days after

Now they start to realise what they have committed to and the difficulties of such a plan.

The Belgians are not concerned. They are at home, it's a short trip to Brussels for the reunion.

The Greeks are not concerned either, as they will have to fly no matter what. At present, there are no international train connections in Greece. Before the austerity reforms hit the country in 2011 there were links with Belgrade, Sofia and Bucharest. There was even a night train between Thessaloniki and Istanbul (useful for a potential Orient Express comeback, but not for our friends).

Our Latvian friend is also feeling left out, as there are no train connections at the moment. There is a large railway project underway to connect all Baltic capitals with Warsaw, called "Rail Baltica". It is, however, expected for 2030. In the design phase, everything seems possible, even building the largest underwater tunnel to link Helsinki and Tallinn. But in practice, the project is not going well, and while Latvia and Lithuania have a lot of interest, Poland doesn’t seem to care.

So far, so bad. Who among them still has options open? It seems that students with the following origins are the fortunate ones that can still do the trip by train and respect their oath:

- Seville, Spain

- Stockholm, Sweden

- Edinburgh, Scotland

- Bucharest, Romania

- Bari, Italy

Travelling in Europe by train

Our friends are trying to replace a plane trip with a train trip. We are going to explore which options they have, and as we go, we will identify the bottlenecks and issues that rail travel has in Europe.

Some Erasmus students are already using the train to reach their host universities. "Erasmus by Train" is a student organisation helping out to plan train trips, contacting universities to promote sustainable travel, and pushing their ideas among train operators and European policymakers. We talked with two of their members, Carl Schüppel and Maximilian Häntzschel, and for them, if you’re an Erasmus student, you have the opportunity to start your adventure right at the departing station. Don’t just fly to your destination, enjoy the slower trip.

There are, however, forces that go in different directions. For instance, the Erasmus Students Network has a partnership with Ryanair: students get a 10% ticket reduction and a free 20 kg check-in bag.

So we face one question: is it feasible to travel throughout Europe by train? We will look at prices as well but with a twist. More on this at the end.

Let's rail on!

Trip #1: 2.000 km - SEVILLE - MADRID - BARCELONA - PARIS - BRUSSELS

The Spanish leg of the journey is straightforward. It starts with the high-speed line Seville-Madrid, the first one built in Spain, in 1992. Today, the high-speed train is the default means of transport between these cities, offering 10 times as many seats as the plane connection. We then switch to the segment Madrid-Barcelona. Open since 2008, it's also a commercial success, with approximately 60% of the traffic between the cities and three operators serving the route (the Spanish RENFE, the French SNCF subsidiary Ouigo, and the partially-owned-by-Trenitalia Iryo).

There are even two daily services Seville-Barcelona without a stopover in Madrid, covering 1.000 km in less than 6 hours. We reach Barcelona with our minds set on crossing the border in the next service, the 7-hour high-speed daily service to Paris. Except that the train from Seville arrives at 14:45, and the one to Paris leaves... 13 minutes earlier.

Issue #1 - Connections

On a busy line like this one, you could still make it. Do Seville-Madrid a couple of hours earlier, then link with the Madrid-Barcelona, and you're on time for your Barcelona-Paris. Because of that 13-minute difference, your trip is now 2 hours longer. On less crowded lines, you might have to spend the night somewhere.

So we boarded the train in Seville at 6:40, it's now 21:18, and we're in Paris. We're just 1 hour away from Brussels! But crossing Paris is a problem in itself, no matter which means of transport you use. We have to change stations (from Gare du Lyon to Gare du Nord). And the latest service to Brussels runs at 21:25... Bad connections, here we go again.

Seville - Brussels could be a 15h train trip, but without good connections, you inevitably have to spend the night en route, and it becomes a 22h one. Well, it's still doable.

Trip #2: 1.500 km - STOCKHOLM - COPENHAGEN - HAMBURG - COLOGNE - BRUSSELS

Stockholm is a bit closer to Brussels, 1.500km away, but it has something that enables easier travel: a night line that connects it with Germany. Board the train in the afternoon in Stockholm and 13 hours later, without changing trains, you're in Hamburg, in 16 hours in Berlin.

Two companies are serving this night route: the state-owned SJ (Swedish Railways, with their Euronight service) and the smaller private operator Snälltåget.

From Hamburg we need to travel to Cologne (5h), and from there to Brussels (2h). If you can adapt to the train timelines, and you're lucky with the connections, you might be able to do the full trip with 3 trains in around 24 hours.

Issue #2 - Tickets and delays

Tickets are sold out on the night line Stockholm - Munich for the next month, in both companies. But that's just one leg of the trip. You need as well Deutsche Bahn tickets to Cologne, and Thalys tickets to Brussels. There are many companies involved, but no central website where you can book your entire trip. Today, some websites (RailEurope, TrainLine) integrate many operators, but not all.

This is the “booking fragmentation issue” and lack of cooperation among companies is a big part of it. Maartje Eyskens, an IT expert and train lover, reminds us that companies used to cooperate, as in the old service from Barcelona to Paris, that SNCF and RENFE delivered together. But recently, they have been pitted to compete against each other, and RENFE will sell you its tickets, but not OUIGO /SNCF ones. This goes against the interest of the passenger.

What’s the solution? Mark Smith is the Man on Seat 61, the main Internet reference on train travel in Europe. He mentions the model of the UK as something that could be scaled up. There are 20 rail operators there, and all of them are obliged to sell you tickets from everyone else. In Italy, the same already happens on the route Milan-Rome: you can get tickets from 2 operators on each other’s websites (Italo and Frecciarossa).

Can this integration be achieved? Björn Stockhausen is an advisor for the Greens in the European Parliament. He has been travelling across Europe without flying for the last 4 years. According to him, we need political pressure to facilitate agreements among companies to get a central ticketing system and arrangements in case of delays.

Because delays can and will happen and passengers need to be protected. Today, train passengers’ rights are not strong enough. If your Snälltåget night service arrives late for your DB connection in Hamburg, you'll have to buy new tickets for the following available service. Travelling in the other direction and missing the night service can be even more problematic. The Man on Seat 61 summarises the issue: “Lower passenger rights mean longer travel times”.

Another aspect of this problem is reservations. There are two philosophies for ticket selling: tickets with a reserved seat, or without. In Spain, France and Italy when you get your ticket you always have a seat with it. In Germany and other countries, you can get a ticket with or without a seat reserved. No seat reservation (and an extra fee for flexibility) means that you can finish your meeting later and jump on the next available service. This means as well that you might need to stand. But at least, you travel. Which model is better? Maartje Eyskens’ approach is that it’s better to sell a “ticket for a route” rather than a “seat on a train”.

Live from IC 1190, Hamburg-Copenhagen, served by Deutsche Bahn

Lena Widefjäll and Marc Giménez work in Brussels for the Greens in the European Parliament and are regular travellers on two train routes: Brussels - Stockholm (to take their kids to see her family), and Brussels - Barcelona (to see his). When we asked them for feedback for this article they were precisely travelling and offered us a sort of live reporting.

As if they were Erasmus students, their adventure started at the departure station. They planned to spend the night in Copenhaguen to show the Little Mermaid to their two small daughters. They prepared and booked a 6-train trip via Deutsche Bahn’s website. On other occasions, their trip was faster, but this time there were disruptions due to rail works in Germany (and the Snälltåget was full). They shared their compartments with nice people and less nice ones. They had spare time for tourism in their connection in Aachen but had to run across the platform (with the kids and the luggage) to change stations in Hamburg. They received an email saying that their Hamburg-Copenhaguen train had been cancelled, and they were using a DB website that plans trip alternatives based on your live location (onboard). But to their surprise, their IC 1190 was restored and ended up with just a 15’ delay hitting Copenhaguen right past midnight. Marc summarised it like this: “Long-distance train travel should be suitable for everyone, not only for the brave".

Trip #3: 1.000km - EDINBURGH - LONDON - BRUSSELS

Edinburgh used to be near. From there you get to London in 4 hours, to Paris in 7, and if you push it you can reach Milan at the end of a 16-hour trip. Edinburgh-Brussels is a mere 1.000 km trip with the only complication of switching stations in London... and Brexit.

From Scotland to London there are two options with a similar price: the daily train, or the sleeper. For our trip, there's no need to spend the night, but it's worth mentioning the Caledonian Sleeper service. The cars are new, delivered in 2019. Just like in a hotel, rooms are open with magnetic cards. Some of them are even double beds. There is a restaurant car. It's a remarkable night train.

From London to Brussels we take the classic connection below the sea: the Eurostar. The 2-hour trip takes more or less as long as the queue at the brand new EU border in London St Pancras.

Issue #3 - Interoperability

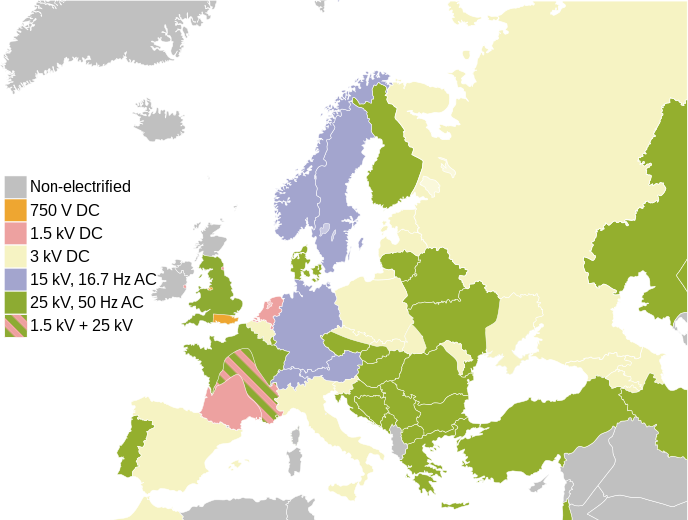

Crossing the waters of the English Channel invites us to discuss the interoperability of train systems:

- Electrification of the line. For their service Brussels-Amsterdam-Berlin, European Sleeper is leasing a locomotive (the Alstom Traxx F140) that can work on the three different electrification systems of Belgium, the Netherlands and Germany.

- Languages spoken by the engine drivers. Spanish train drivers entering France need to speak French (and vice versa).

- The train management system, and in particular, the signalling system. The whole European rail network should adopt the European Rail Traffic Management System in 2040.

- Rail gauge. Both Spain and Portugal have the “Iberian gauge” in their national networks and the “standard” one on the high-speed lines. The Baltic states have the “Russian gauge” while Rail Baltica will use standard.

- Loading gauge. Or in other words, how large your tunnels have to be for a train to pass. Swedish trains turn out to be wider than the rest, so to allow a Swedish train to reach a German station the railway needs to be adapted.

All these aspects are being gradually standardised to reach the “Single EU Railway Area”.

Maartje Eyskens doesn’t see here a big problem. She says that technical interoperability was solved 50 years ago. Locomotives can be changed in the middle of the route, they can incorporate several signalling systems, rolling stock exists that can run on different rail gauges and cross-border routes are served by freight lines without issues. But passenger operators need to want to do it.

Trip #4: 2.200km - BUCHAREST - BUDAPEST - VIENNA - FRANKFURT - BRUSSELS

From Bucharest, two night trains go into Central Europe following the same route. One stops in Budapest after 15 hours, and the other one continues for 3 more hours until Vienna. That's the long leg of this trip. From Vienna, things get relatively easier. A connection to Frankfurt and another one to Brussels will add "only" 11 hours to the trip. That's Bucharest-Brussels in less than 30 hours and just 3 trains.

The "tourist" approach appears as an interesting option in this route. After one night onboard, spend the day roaming around Budapest or Vienna, and then jump on a second night service to Brussels. That would take the trip to 44 hours, including a day of tourism in Central Europe and 2 nights onboard.

Vienna could be named the European capital of night trains.

The Austrian operator ÖBB is currently the European leader in night services, serving 24 routes through the "Nightjet" brand. The story of Nightjet is remarkable, and it portrays several key aspects of the debate around night trains in Europe.

In 2015 Deutsche Bahn was running several night services. But the introduction of further high-speed lines during the day reduced the demand for night trains. Deutsche Bahn didn’t manage to make them profitable. So, in 2016, they sold their night cars and routes to ÖBB. Today, traffic is growing and they have commissioned new sleeper trains, which will soon be delivered by Siemens. See virtually how the new Nightjet trains look from the interior.

Issue #4 - Rolling Stock

The main limiting factor for ÖBB’s Nightjet to expand is precisely the lack of rolling stock.

New companies attempting to set up routes face the same issue: they don't have new trains. They have to buy or rent old cars and refurbish them to meet the current regulations (like fire protection or emergency exits). But in terms of comfort, they're behind (small number of power sockets, no Wi-Fi connection).

Train travel in Europe used to be more common years ago. So much so, that a standard carriage was designed which could run in several countries. This is the Eurofima coach. 500 of these standard carriages were delivered in the ’70s to 6 European train operators for their international services. Is it time for a “Eurofima version 2”?

Trip #5: 1.800 km - BARI - TURIN - PARIS - BRUSSELS

The Italian night service, called Intercity Notte, is also relevant, serving 9 lines. Starting South, in Bari, we can get on board the night service at 18:30 and be in Milan the following day at 7:05.

Milan is directly connected with Paris with 2 daily trains, but the earlier one already left at 5:53 and the other leaves in the afternoon. So we have to take another service to Turin, and from there take one of the 6 direct daily trains to Paris.

This time, we'll hit Paris on time to switch stations, get the connection to Brussels and arrive by 22h, 26 hours after having started the trip.

Issue #5 - The lack of night trains

In this case, we managed to combine a night train with a day train, which is close to ideal to cover long distances by rail. To cross Europe, and to be competitive against the plane, it's crucial to have many night train options.

Night trains used to be more common. As a young adult, I used them to travel through Spain. I remember the "Estrella Costa Verde" entering the Oviedo station, with only 2 cars. During the night they merged the trains from other cities, and in the morning the full 20-car convoy was entering majestically in Madrid. But these services have been removed following the expansion of the high-speed lines.

One relevant night service discontinued during the pandemic and for which there is no high-speed alternative is the “Trenhotel” Lisbon-Madrid. It used to take more than 10 hours to cover 600 km and it was always loss-making.

We have seen this in other countries too: Germany, also due to high-speed new lines, Greece, due to austerity reforms, and France, which also closed services during the pandemic.

Night trains have been in decline. But is it still the case?

ÖBB is now ordering new trains for Nightjet. The start-up Midnight Trains also decided to order brand-new cars, as they explain in their weekly newsletter. Recently, the Brussels-Berlin service was initiated by another start-up called European Sleeper. They want to connect as well Barcelona and Amsterdam (bypassing Paris and being helpful for our trip Seville-Brussels) and extend the Berlin connection up until Prague. Their rolling stock is 40 years old, and they don't have a dining car. Yet, because they’re looking for one as dining onboard is probably one of the most attractive parts of a night trip. By the way, do you know that you can invest in European Sleeper starting at 250€?

Price is not the (first) problem

Up to now, we have tiptoed around one issue which is crucial for our students: price.

Seville - Barcelona - Paris - Brussels can cost around 400€ one way. We could have started by saying this and saved ourselves the work of writing the rest of the piece. But that’s not the end of the story.

If night trains to Barcelona were re-established, they could offer cheaper seating than the high-speed line and then become more affordable for students.

We could also enter into a rant against unfair subsidies to plane companies (and we would be right). But instead, we want to slide in a different argument about price.

It comes from Jon Worth, an expert in Cross Border Rail. He travels regularly across the borders of the EU Member States and narrates his experience through his Mastodon account.

Here’s his argument broken down:

Current night trains (and some daily routes) are already full

If you reduce ticket costs for the Nightjet or the Paris-Bruxelles line, you will get "different" people travelling, but not "more" people travelling (because the trains are full anyway).

So you have to increase capacity before being able to bring prices down.

We discussed this idea with Jon, and he asked us to look at the bigger picture. Who are railways for? What is an acceptable price? He says there are two price models. Under the classic state model prices are kept low via subsidies. This is used by Austria, Germany and the Czech Republic. On the other side, the competition model introduces new operators to bring the costs down. This is what Spain and France are doing with their high-speed lines.

Which one should be used? According to him, it depends on the route. We reviewed together the following:

Milan-Rome. A connection between large cities with very good track infrastructure where many more trains could run. Competition would work here.

Amsterdam-Brussels. The route is already at capacity. New operators won’t be able to bring cheaper prices.

Paris-Brussels. The worse of both worlds: a state-owned monopoly (Thalys) but prices are set via the market.

Price for students

Coming back to the case of students, the Erasmus by Train people offered good arguments about why the train can still be competitive today:

No luggage weight limit. This is important for Erasmus students whose winter clothes alone weigh more than 20 kg.

If you have enough information, are young enough to qualify for discounts, and book well in advance, you can find connections that are cheaper than flying.

Finally, they argue that students should not be forced to choose between affordability and climate. Together with the Erasmus Student Network, they propose the free Erasmus+ train ticket.

Europe needs more train connections

How can trains compete with planes? The Man on Seat 61 mentions the magic number of 3 hours. If a train trip takes 3 hours, it is competitive against a flight that takes 1 hour plus getting to and from the airport plus the security screening. If you add to this the longer and longer times spent at security, and the possibility to work during your train trip, then it can slide up to 4-5 hours. If you want to travel further, an 8-hour high-speed trip won’t be ideal, you should have a night train available.

Europe needs more trains, more night trains, and more capacity in both to enable a larger share of its citizens to travel without flying.

The European Commission is aware of this. To be precise, one part of the hydra with a thousand heads that is the European Commission is aware of this and has announced support for 10 cross-border rail services.

We can see which ones of those will be relevant for our students.

Top of the list is the Barcelona-Amsterdam (bypassing Paris) night service by European Sleeper.

For our Eastern Europe route, all improvements in the Romania-Hungary-Austria link will result in better and faster service.

Coming down from Stockholm, there will be new and enhanced services linking Copenhagen and Berlin.

And to carry travellers from and to the South, a new night service will link Paris and Milan, extending to Venice. The France-Italy market seems to be screaming for new services, and Midnight Trains wants to serve it.

In the list, also the missing Madrid-Lisbon link will hopefully be soon back again in a competitive fashion.

We also discussed with Jon Worth this EU plan. He says it’s the best thing done in European rail transport in ages. Although that doesn’t hide a certain lack of vision by the European Commission. After all, those lines have been proposed by the industry, not by the public administration. From his perspective, the biggest limiting factor to increasing train travel today in Europe is not the lack of new tracks, but the lack of new trains, and that’s where the EU effort should be focused.

What will our friends do?

It is still difficult and expensive to travel by train, but it’s doable. It depends on how much time and money you want to spend to swim against the current and avoid flying. Travelling by train means fighting against the structural situation.

But the tide is turning.

Fast forward to July 2024, the location now is the Brussels South station, end of the line of the Eurostar. Our friend from Edinburgh is the first to arrive. Buying a couple of months in advance, he got a €60 seat on the Caledonian Sleeper and a 58€ on the Eurostar. The roaming on his phone seems off and messages are not getting in. How has been the trip for the others?

At the other end of the station corridor, he suddenly sees the Romanian group, having just disembarked the night train from Vienna. They have been travelling for almost two days and spent the day before sightseeing. It was so good, they almost missed the departure of their second night train.

No one knows where the Spanish colleagues are. To compensate for the expensive high-speed tickets to cross Spain, they went for the cheaper option to do Paris-Brussels: a slower service changing trains at Lille. They eventually appear in the middle of the afternoon without anyone knowing exactly on which train they arrived. Later on, they will confess to having messed up their connection due to their lack of sleep, and eventually bought bus tickets to reach Brussels.

The team from Sweden make it right after. They look more relaxed than the rest. They paid less than 100€ for a couchette bed in the night service, and a good night's sleep made the difference.

Almost everyone has arrived by now. They decide to wait at the station for the last friends to arrive from Italy. All of them congregate on the platform waiting for the last service of the day from Paris. They’re in for a surprise. It’s not only the Italians that come out of the train but the Greeks too! Without telling anyone, they asked Erasmus by Train for advice, met at the Greek port of Igoumenitsa, and took the night ferry to Bari. From there onwards they joined the Italian trip plan. This added one more full day to their schedule, but here they are!

Where do we get from here?

This story is, of course, fictitious. Because we have placed it in 2024, and written it based on 2023 data. Allow us to be optimistic and say that next year things might be easier.

Soon there will be more options to cross Europe by train. Maybe people will be able to buy a single ticket from end to end that includes several trips from different companies. They will jump on a train to eat a nice dinner and spend a night comfortably crossing the continent in a brand-new sleeper car. Humble, hidden improvements on interoperability will continue to make it transparent for the traveller. Timetables will be adjusted so that daily connections will wait for night trains to arrive, and vice versa. If delays happen (which they will), passengers will be accommodated in the next available service. All travellers, even students, will find a seat adjusted to their budget.

Friends from all corners of Europe will be able to reunite, having more options to do so than in the good old grey city of Brussels.

Lots of great detail there! 👏👏 Irish students would have been interesting, but then I suspect they’re behind the Ryanair discount somehow...